Improbotics

I am currently at the 14th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment (AIIDE'18) held at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, AB, Canada on November 13-17, 2018.

I am very excited to be in my own home town presenting, in collaboration with Piotr Mirowski, Improbotics: Exploring the Imitation Game using Machine Intelligence in Improvised Theatre.

Theatrical improvisation (impro or improv) is a demanding form of live, collaborative performance. Improv is a humorous and playful art-form built on an open-ended narrative structure which simultaneously celebrates effort and failure.

We believe it is an ideal test bed for the development and deployment of interactive artificial intelligence (AI)-based conversational agents, or artificial improvisors. This case study introduces Improbotics, a theatre show and experiment, featuring human actors and artificial improvisors. This is an experiment that we presented in “Improvised Comedy as a Turing Test”, Mathewson and Mirowski, 2017.

We have previously developed a deep-learning-based artificial improvisor, trained on movie subtitles, that can generate plausible, context-based, lines of dialogue suitable for theatre. If you have not seen it, check out “Improvised Theatre Alongside Artificial Intelligences”, Mathewson and Mirowski, 2017.

In this work, we have employed it to control what a subset of human actors say during an improv performance. We also give human-generated lines to a different subset of performers. All lines are provided to actors with headphones and all performers are wearing headphones.

This paper describes a Turing test, or imitation game, taking place in a theatre, with both the audience members and the performers left to guess who is a human and who is a machine. In order to test scientific hypotheses about the perception of humans versus machines we collect anonymous feedback from volunteer performers and audience members.

We asked the five questions below to performers (and audience by replacing ‘you’/‘your’ with ’the performers’) to examine the various facets of the performance:

- (possibility to act) How much were you able to control events in the performance?

- (realism) How much did your experiences with the system seem consistent with your real world experiences?

- (evaluation of performance) How proficient in interacting with the system did you feel at the end of the experience?

- (quality of interface) How much did the control devices interfere with the performance?

- (possibility to examine the performance) How well could you concentrate on the performance rather than on the mechanisms used to perform those tasks or activities?

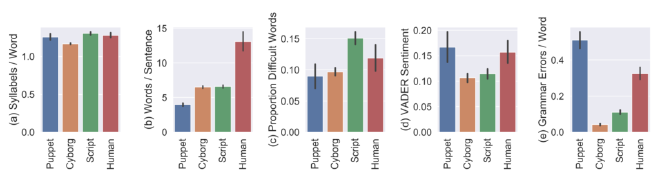

Our results suggest that rehearsal increases proficiency and possibility to control events in the performance. That said, consistency with real world experience is limited by the interface and the mechanisms used to perform the show. We also show that human-generated lines are shorter, more positive, and have less difficult words with more grammar and spelling mistakes than the artificial improvisor generated lines.

There were additional interesting findings, including that audiences rated the performers as having more control of the events during the performance than the performers. We collected feedback from performers and summarized it into four main themes:

- Improvising with the system is more work

- The system cannot tell complete stories.

- Forces you to be a better improvisor.

- Like performing with a novice improvisor

Also, there are three particular areas of future research which desire some attention:

- The nature of the deception before, during, and after the show. While the imitation game as presented by Alan Turing was focused on deceiving a single judge, Improbotics frames the deception in an ongoing theatrical performance. This requires addressing the perception and decision making of an entire audience.

- The lack of contextual consistency of these systems – this particular area is something that Markus Eger and I took a step towards addressing with “dAIrector: Automatic Story Beat Generation through Knowledge Synthesis”, Eger and Mathewson, 2018.

- Improving the timing of these systems. Humans are often taking turns talking based on predictions of the next line of dialogue from the others in the conversation. We are quite sensitive to the speed of conversation, and systems which lack this immediacy are quickly identifiable.

If you want to get started making an interactive storytelling system of your own, start with Jann. Jann is a text input / text output chatbot builder which allows for fast interaction with large bodies of text.

If you want to dig deeper into this work, you can check out the paper, and see the project website for details on upcoming shows and more information.